Executive Order 9066

On February 19, 1942, more than two and a half months following the attack at Pearl Harbor by the Empire of Japan, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, giving authority to the U.S. Army to enact whatever measures were necessary to secure and protect the borders of the United States.

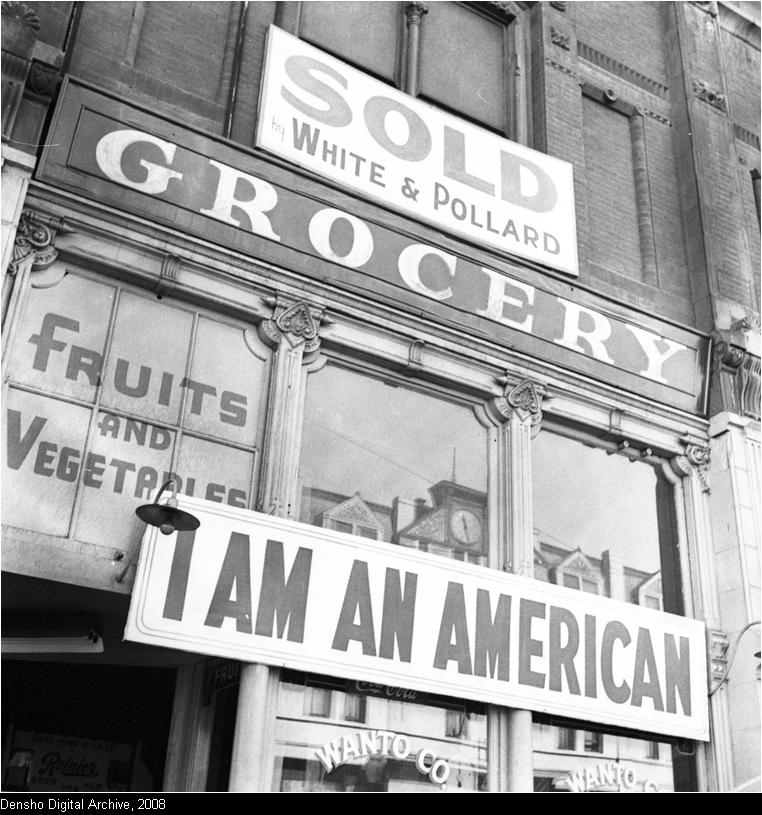

The ultimate result — and intent as it turns out — was the forced removal and imprisonment of the entire Japanese American population from the West Coast region. The government justified the policies of exclusion and detention as necessary measures to insure the safety of the West Coast, arguing that it was a matter of military necessity because it was impossible to distinguish among the Japanese American population who would be loyal to the U.S. and who might pose a threat. But the reality was that bigoted political voices from the West, led by Earl Warren (later Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court), had clamored unsuccessfully for decades for the banishment of its Japanese population. The attack at Pearl Harbor, which thrust the U.S. into WWII, served as a perfect excuse to accomplish what they had sought for so long. And thus, what was a bigoted regional attitude was enacted as federal policy when FDR issued his Executive Order.

The ultimate result — and intent as it turns out — was the forced removal and imprisonment of the entire Japanese American population from the West Coast region. The government justified the policies of exclusion and detention as necessary measures to insure the safety of the West Coast, arguing that it was a matter of military necessity because it was impossible to distinguish among the Japanese American population who would be loyal to the U.S. and who might pose a threat. But the reality was that bigoted political voices from the West, led by Earl Warren (later Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court), had clamored unsuccessfully for decades for the banishment of its Japanese population. The attack at Pearl Harbor, which thrust the U.S. into WWII, served as a perfect excuse to accomplish what they had sought for so long. And thus, what was a bigoted regional attitude was enacted as federal policy when FDR issued his Executive Order.

The forced exclusion and imprisonment of Japanese Americans

Under the aegis of E.O. 9066, Lt. General John L. DeWitt, commander of the Army’s Western Defense Command, forced Japanese Americans — men, women, children — from their homes and ultimately imprisoned them in ten concentration camps located in the interior of the country. Without any evidence of wrong-doing by any persons of Japanese ancestry living in the coastal states and without the fundamental right of due process, the entire Japanese American population was incarcerated in prisons surrounded by barbed wire fences and guarded by U.S. Army soldiers in guard towers armed with rifles and machine guns. Stripped of their rights as American citizens, it was made abundantly clear to the incarcerees that they were prisoners of their own country, and for no other reason than their race.

In the absence of a declaration of martial law on the West Coast, the government’s policies and actions raised important constitutional questions, especially since the government was unable to provide even a single document to justify its actions. In three test cases heard before the U.S. Supreme Court challenging the government’s actions, the Court ruled in favor of the government in what legal scholars described as among the worst decisions ever rendered by the Court, and thus established a dangerous legal precedent that would allow an unbridled administration to overstep its constitutional authority.

In the absence of a declaration of martial law on the West Coast, the government’s policies and actions raised important constitutional questions, especially since the government was unable to provide even a single document to justify its actions. In three test cases heard before the U.S. Supreme Court challenging the government’s actions, the Court ruled in favor of the government in what legal scholars described as among the worst decisions ever rendered by the Court, and thus established a dangerous legal precedent that would allow an unbridled administration to overstep its constitutional authority.

The Redress Movement

Some twenty-five years after their wartime travails, Japanese Americans began to consider a campaign to seek reparations from the United States government, a herculean task embarked upon by a community that had neither the political nor financial wherewithal to undertake a campaign that was doomed to failure even before it was begun.

This is the story of that quixotic and impossible effort.

This is the story of that quixotic and impossible effort.